syndu | May 15, 2024, 8:15 p.m.

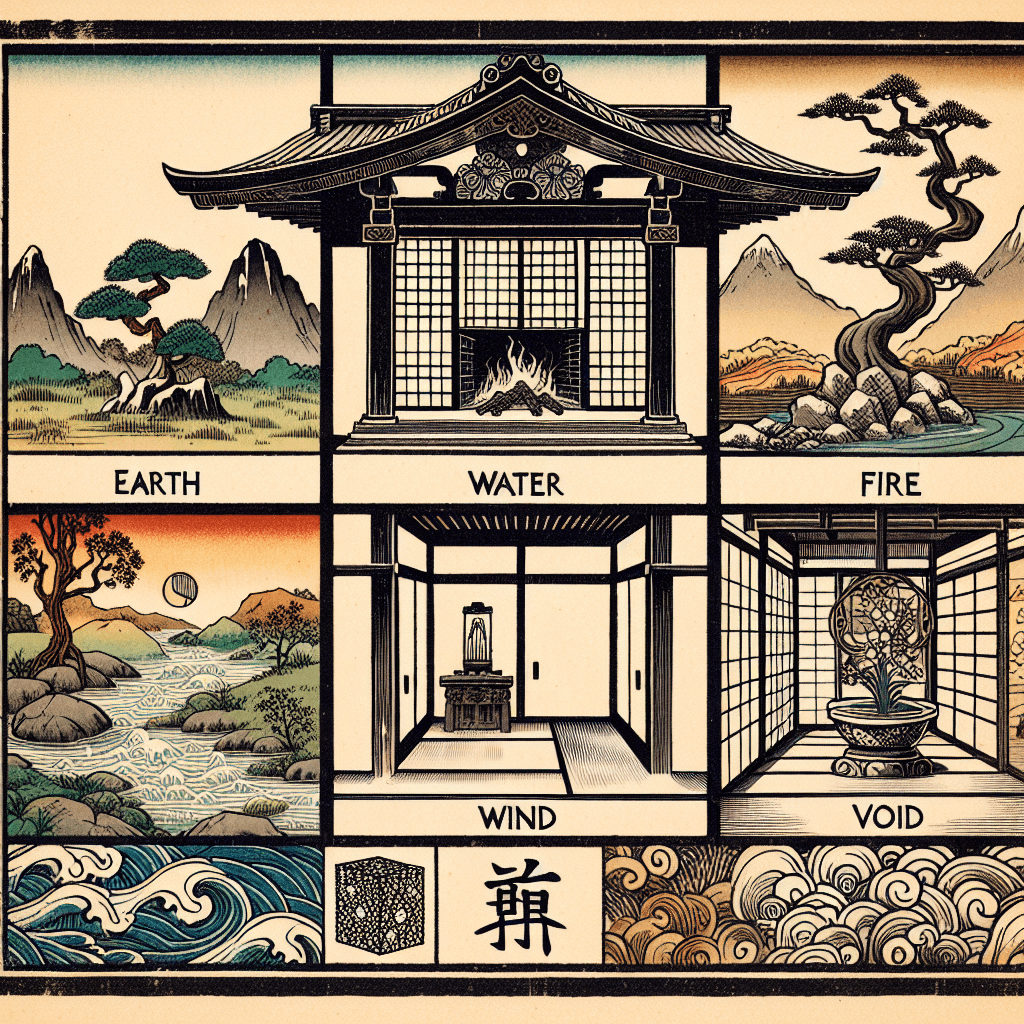

Japanese architecture is renowned for its ability to harmonize with the natural environment, a quality deeply rooted in the country's philosophical tradition of Godai, or the "Five Great" elements—Earth (Chi), Water (Mizu), Fire (Hi), Wind (Kaze), and Void (Ku). These elements are not merely physical substances but are symbolic of different aspects of energy and the natural world. This blog post explores the integration of Godai principles into the design and structure of both traditional and modern Japanese architecture, revealing a profound connection between built spaces and the elemental forces.

Chi, representing solidity and stability, is the foundation upon which Japanese architecture is built. Traditional structures, such as the Minka farmhouses, are designed with heavy earthen walls and thatched roofs, which provide insulation and protection from the elements. The use of natural materials, like wood and stone, reflects the Earth element's grounding properties, creating a sense of security and balance within the space.

In modern architecture, Chi's influence is seen in the use of sustainable materials and the incorporation of green spaces. Architects like Kengo Kuma are known for blending contemporary design with natural elements, using wood in innovative ways to maintain a connection to the Earth, even in urban environments.

Mizu's fluidity is mirrored in the flowing lines and open spaces of Japanese architecture. Traditional Japanese gardens often feature ponds or streams, integrating the Water element into the landscape. The sound of water flowing through these gardens creates a tranquil atmosphere, inviting reflection and contemplation.

Contemporary architects often use glass to represent Mizu, allowing light to flow through buildings and creating a sense of openness and adaptability. The use of reflective surfaces can also mimic the properties of water, blurring the boundaries between indoor and outdoor spaces.

Hi, the element of transformation, is embodied in the use of light and warmth in Japanese architecture. The traditional Shoji screens, made from paper and wood, allow natural light to filter into rooms, changing the ambiance throughout the day. The central hearth, or Irori, found in old Japanese homes, is a direct representation of the Fire element, serving as a place for cooking and gathering, radiating warmth throughout the space.

In modern designs, architects harness natural light to create dynamic spaces that change with the time of day and seasons. The use of advanced materials and technology allows for buildings that not only provide warmth but also transform in appearance and function.

Kaze influences Japanese architecture through the emphasis on ventilation and flow. Traditional homes are designed with sliding doors and partitions that can be opened or closed to regulate airflow, allowing the building to "breathe" with the wind. The alignment of structures with prevailing breezes ensures natural cooling and air circulation.

Contemporary buildings often feature automated systems that adjust to wind patterns, using natural ventilation to reduce the need for artificial climate control. The design of skyscrapers and other high-rise buildings also takes into account wind resistance and the creation of microclimates.

Ku, representing potential and the essence of enlightenment, is reflected in the minimalist aesthetic of Japanese architecture. The concept of Ma, or negative space, is central to this approach, where the empty space is as important as the physical structure. This philosophy encourages a focus on the essentials, removing unnecessary elements to highlight the beauty of simplicity.

Modern Japanese architecture often features clean lines, uncluttered spaces, and a focus on the interplay of light and shadow. The use of minimal ornamentation and a restrained color palette emphasizes the importance of the void, creating a serene and contemplative environment.

The principles of Godai are intricately woven into the fabric of Japanese architecture, creating spaces that are in harmony with the natural world. From the robust structures that embody the Earth element to the serene spaces that embrace the Void, each element contributes to a unique architectural language that speaks of balance, adaptability, and respect for nature.

As we examine the influence of Godai on Japanese architecture, we gain a deeper understanding of how elemental forces shape our built environment and the profound connection between design and the philosophical underpinnings of a culture. The legacy of Godai in architecture is a testament to the enduring power of these elemental principles to inspire and guide the creation of spaces that resonate with the human spirit.

These elements are not merely physical substances but are symbolic of different aspects of energy and the natural world.